Literary Reading Groups Add Depth and Value to the Research Process

By Lauren Olster

Students who are earning advanced academic degrees find many ways to enhance their research and scholarship. They rely on professors to mentor them and guide them through the process. They engage and collaborate with other graduate students who have similar interests. And they read. A lot.

That’s where the English department’s reading groups can help shape students’ critical thinking with the texts they use to develop their theses or to discover other outlets for their various interests.

That’s where the English department’s reading groups can help shape students’ critical thinking with the texts they use to develop their theses or to discover other outlets for their various interests.

“Graduate students are interested in becoming professionals in the field in some way or another,” Literature, Media, and Culture Program Director and Professor Robin Goodman says. “Often, this means they are learning to be academics, to research, publish, and teach.

“The reading groups give the students the opportunity to pursue ideas related to their own research that might turn into an article or other professional endeavor.”

The reading groups are one-credit courses designed to facilitate conversation between students and faculty dedicated to a specific subject. Groups such as Africana Studies, Re-reading Foucault, and Queer Studies focus on specialized topics that might relate to graduate students’ unique studies.

One of the reading groups is Environmental Literature, which Emilie Mears and Paige Wallace co-founded in the fall of 2017. Both are Ph.D. students in the literature program and both focus on eco-critical scholarship.

In person, Mears is what you would expect of an environmental enthusiast. Wearing a tree branch-patterned skirt and a flower-adorned hat, Mears sits in her Williams Building office.  The walls of her cubicle are strung with colorful, nature-inspired drawings, a calendar of natural landmarks, and personal pictures of mountains and waterfalls from her various backpacking trips over the years.

The walls of her cubicle are strung with colorful, nature-inspired drawings, a calendar of natural landmarks, and personal pictures of mountains and waterfalls from her various backpacking trips over the years.

Mears uses much of her time at FSU teaching and spreading awareness about the ecosystem by finding connections between nature and literature. On the desk behind her office chair is a neat stack of environmental and American literature textbooks interspersed with novels and a copy of Grammar Girl.

“One year [my friends and I] went on a backpacking trip from the South Rim to the North Rim and then back to the South Rim; it took us six days,” she says, pointing to a photo of the Grand Canyon, among others. “Yellowstone, Bryce Canyon, Rocky Mountain National Park…” she goes on rhythmically. She seems to be in another world as she remembers the experiences.

After coming to FSU in 2015, Mears and Wallace joined forces to form the graduate-level environmental literature course that came to fruition in the fall of 2017 and now meets five times a semester. In the meetings they discuss readings, complete hands-on activities, and take outdoor excursions where they like to bond on a more personal level with nature and one another.

The pair noticed when their graduate program coursework examined issues such as gender, politics, feminism, and racism that there was overlap with the term "nature" or "natural."

“A lot of these topics came down to this relationship between place and personhood—or what I like to call ‘word and world,’” Mears says.

They started the literature reading group, Mears says, so that at least the two of them could meet to talk about some of the critical works of ecocritcism’s  founding—from scholarship and primary texts.

founding—from scholarship and primary texts.

“We wanted to make sure we had an outlet,” says a smiling Mears. “We wanted to have an opportunity for people of interest to have these conversations."

“Outsiders are welcome,” she adds, in addition to those officially enrolled in the class.

Mears and Wallace work together to assign a balance of scholarly articles, primary texts, and American literature to their students so they can understand the undervalued connection between the texts and the physical world.

At the group’s first meeting, students discussed the foundation of ecocriticism as well as some of the primary texts used in the field, including ones by authors Greg Garrard and Lawrence Buell.

“We wanted to get an idea of how people think of space and place and what goes on through their minds regarding access within communities,” Mears says.

The most important goal to Mears, on both a personal level and as an educator, researcher, and environmentalist, is to have and spread mindfulness regarding the Earth.

“I know this term is so outdated but I like this idea of mindfulness, of taking some sort of consideration of what I’m using and what I’m throwing away,” Mears says, while rubbing her temples. By example, she then takes out a flowery beige cloth from a drawer and unfolds it across her lap to explain that she uses it with meals in place of paper napkins.

From buying animal-friendly eyeliner and picking up trash to thinking about the unfair living conditions of less-privileged people in an increasingly dangerous Earth, Mears constantly tries to improve her mindset and actions. Ultimately, she wants people to motivate themselves through education and action to be more aware, more resourceful, and more understanding of our world.

“You have to get people out of their comfort zones to challenge themselves, because if we’re not doing that then we’re not allowing ourselves to learn. I think important things like protecting ourselves and our environment are worth making us a little uncomfortable,” says Mears, with a chuckle. “Because we’re going to be a heck of a lot more uncomfortable if we just let things continue down the track that they are.”

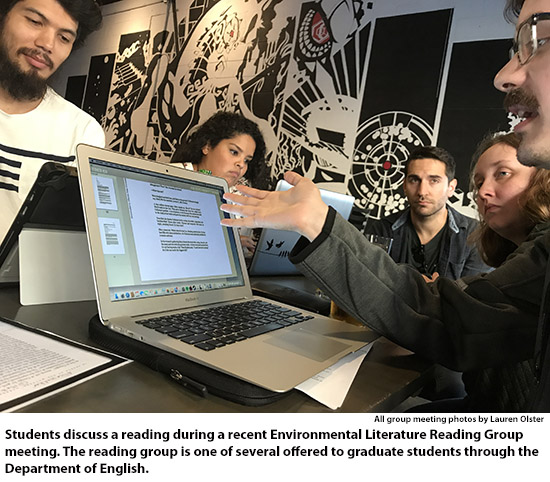

Graduate students discussed the role of race in ecofeminism during the group’s mid-November meeting. Camille Vilela, an active voice in the meeting’s conversations, admitted she had never heard of “eco-literature” before taking this course, which she enrolled in solely out of curiosity.

Aside from attending the meetings, Vilela says she enjoys learning about her surroundings through group excursions, such as last month’s kayaking trip at FSU’s Reservation.

While the discussion flowed, everyone bounced around ideas, speaking to everything from man’s representation of nature to the way society fragments women’s identities, all based on the works of Audre Lorde, Emily Dickinson, Laura Mulvey, Mahasweta Devi, among other writers. The group discussed the stereotypes and constraints of Native women who are bound to nature by Western ideologies. They talked about the way history teaches colonialism as “virgin landscapes needing to be conquered or despoiled,” as well as the evolution of ecofeminism to include people of color and the LGBTQ+ community.

While the discussion flowed, everyone bounced around ideas, speaking to everything from man’s representation of nature to the way society fragments women’s identities, all based on the works of Audre Lorde, Emily Dickinson, Laura Mulvey, Mahasweta Devi, among other writers. The group discussed the stereotypes and constraints of Native women who are bound to nature by Western ideologies. They talked about the way history teaches colonialism as “virgin landscapes needing to be conquered or despoiled,” as well as the evolution of ecofeminism to include people of color and the LGBTQ+ community.

Wallace ended the meeting by calling for a new definition of ecofeminism—to use as a lens with which to read literature—based on the meeting’s dialogue, which led to a new conversation considering the projection of human onto nature.

The hour and a half left few topics untouched, revealing the power of environmental literature to analyze human behavior, yet almost everyone took up Mears’ offer to continue the conversation well past the scheduled end time.

Reading groups such as Mears and Wallace’s serve to enrich the graduate school experience for students looking to go further with and focus more narrowly on their areas of study.

“They [reading groups] give graduate students a chance to look at challenging texts that aren't necessarily part of their regular curriculum by finding others who want to figure them out too,” says Goodman, who recently led a group titled “It Can’t Happen Here: Literature and Fascism in America,” which offered a discussion on Sinclair Lewis’s 1935 book It Can’t Happen Here in addition to other critical perspectives on authoritarianism. “They supplement the classroom.”

The reading groups open for the current semester are listed on the English department's website and can be found here.

Lauren Olster is a senior English major with a concentration in editing, writing, and media. She is earning her internship with the Department of English.