FSU students find fascinating book traces during scavenger hunt

By Sydney Richner

"Here we come a in a

Rooters – tooters

Here are we

Florida, Florida-

Don't you see?”

Mackenzie Broome, a first-year English major, recently found this antiquated University of Florida chant written in a Strozier Library book—denoting a rivalry between UF and Florida State University that dates back approximately 170 years.

This handwritten chant is an example of what’s known as a “book trace.” Broome found the entry in an 1897 edition of John Milton’s Paradise Lost, along with a name listed on its front page.

This handwritten chant is an example of what’s known as a “book trace.” Broome found the entry in an 1897 edition of John Milton’s Paradise Lost, along with a name listed on its front page.

“I found myself going down a rabbit hole of trying to connect the name ‘Grace Godley’ (written on the same page) to the game-day chant,” Broome says.

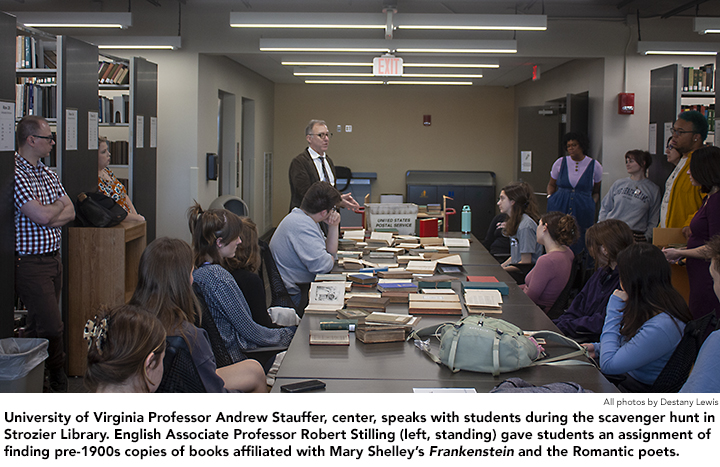

Broome is a student in English Associate Professor Robert Stilling’s Understanding Literary History II LIT 3124 class. On Feb. 9, Stilling’s students participated in a scavenger hunt event on the fifth floor of FSU’s Strozier Library to find more examples of book traces like Broome’s.

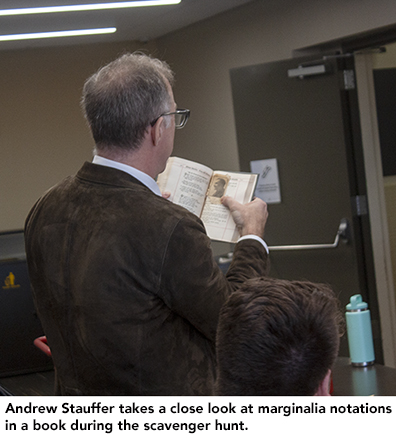

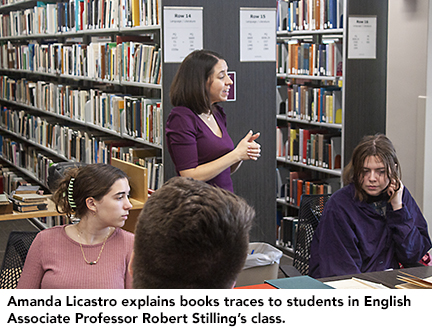

Professor of English at the University of Virginia Andrew Stauffer, and Amanda Licastro, a Digital Scholarship Librarian at Swarthmore College, led the workshop. Stauffer’s and Licastro’s Book Traces project involves discovering original marginalia  notations—book traces—that remain on literary volumes.

notations—book traces—that remain on literary volumes.

Later that day, Stauffer further explored the insight that 19th-century marginalia provides and the need for its preservation in his lecture titled "Book Traces: 19th-Century Readers and the Future of the Library" for the Literature, Media, and Culture Program’s Spring Series on Archival Research.

Prior to attending the workshop in the library, Stilling’s students were tasked with finding pre-1900s copies of books affiliated with Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein and the Romantic poets. The students’ assignment was to find books containing names, dates, or other marginalia denoting their original ownership, and, as a result, they made personal discoveries of their own.

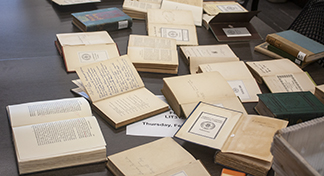

The group collected a stack of books with an array of significant notations; for instance, one book contained a love note to a beloved figure while another listed the names of a classroom full of women students.

“I think it’s really important to understand that ‘literary history’ is not just a history of writing, it’s also a history of reading, and a history of individual reader’s interaction with books as physical objects,” Stilling says.

“I think it’s really important to understand that ‘literary history’ is not just a history of writing, it’s also a history of reading, and a history of individual reader’s interaction with books as physical objects,” Stilling says.

Broome’s copy of Paradise Lost revealed the “history of readers” with, as Broome cites, a little bit of “rabbit hole” digging. The discovery served as an insight to the past, becoming its own historical artifact.

Broome was able to expand upon the book trace she found through a series of internet searches. She uncovered Godley’s graduation information, including her university, Florida State College for Women, and her graduation date, June 10, 1914, in a digital issue of Florida Farmer and Homeseeker. Broome even traced Godley to her years beyond graduation when she worked as a schoolteacher.

Uncovering marginalia enables readers to glean information about their predecessors— those who held the book before them—and the society in which they lived. Stauffer and Licastro, who hosted the scavenger hunt, encouraged the students to find and recognize these books, outside of the workshop. There are many books like this, Stauffer states, noting that “around 12.5% of library books contain marginalia.”

Another undergraduate in Stilling’s class, Linsey Giddens, looked beyond the Strozier Library to complete her assignment. Giddens thrifts old books in her spare time; her submission spotlighted an English composition book, Oral and Written English Advanced Book, from Old South Antique, a local thrift store.

Giddens found lots of “little-kid-like things” within this copy, including crushes’ names, a Valentines card, a Christmas cut-out, and instructions on proper telegram etiquette.

This book is one of “my favorite antiques in my house; I am excited to share [it],” she says.

These little histories are scattered throughout our library and bookstore shelves, and the students’ scavenger hunt findings suggest that we stand to learn more from our books than the contents of their printed text.

Many of them served as communication devices, Licastro says. Prior to the invention of personal computers, there was no such thing as a digital footprint, only traces of handwriting to mark ownership.

Now, each message serves to mark an individual’s place in existence, or to proclaim they once were here: alive and reading, #theywerehere.

Sydney Richner is an English major in the Literature, Media, and Culture Program with a minor in sociology.

Follow the English department on Instagram @fsuenglish; on Facebook facebook.com/fsuenglishdepartment/; and Twitter, @fsu_englishdept