English department welcomes digital humanities scholars to campus to discuss book traces and the future of the library

By Sydney Richner

Florida State University’s English-Literature, Media, and Culture Program recently welcomed to campus two digital humanities scholars for a department-sponsored Distinguished Speaker Event.

University of Virginia Professor Andrew Stauffer and Amanda Licastro, a digital scholarship librarian at Swarthmore College, gave a talk about their Book Traces project in early February.  Stauffer’s and Licastro’s research involves discovering original marginalia notations that remain on literary volumes, particularly of the 19th century.

Stauffer’s and Licastro’s research involves discovering original marginalia notations that remain on literary volumes, particularly of the 19th century.

Their project was inspired by the rise of online commenting.

“Online comments and annotations were coming up around the same time that I made these book trace discoveries with my students,” Stauffer says. “We instantly realized…this has been going on for a long time, just in a different media format.”

This rise corresponded with a growth in the digital humanities, which has pushed the Book Traces team back into the stacks, as online books become increasingly popular.

“Traces help us track a book as a social object,” Stauffer says.

English department faculty members Anne Coldiron, who recently retired from FSU, and Lindsey Eckert, associate professor in the Literature, Media, and Culture Program, forwarded Stauffer’s name as a possible guest speaker for the Distinguished Speaker Event series. Both had read his 2021 publication Book Traces: Nineteenth-Century Readers and the Future of the Library, which is Stauffer’s “‘guided serendipity’ as a tactic in pursuit of two goals: first, to read nineteenth-century poetry through the clues and objects earlier readers left in their books and, second, to defend the value of keeping the physical volumes on the shelves,” according to the book’s publisher.

“This year’s Distinguished Speaker Event was built around a joint effort between the LMC and the Rhetoric and Composition programs to identify a topic that spanned the two programs,” says English Professor Candace Ward, director of the LMC program. “Dr. Stauffer and Licastro’s Book Traces seemed a natural fit.”

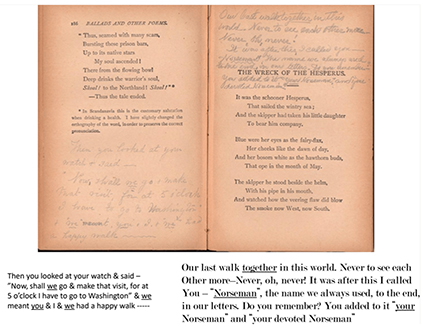

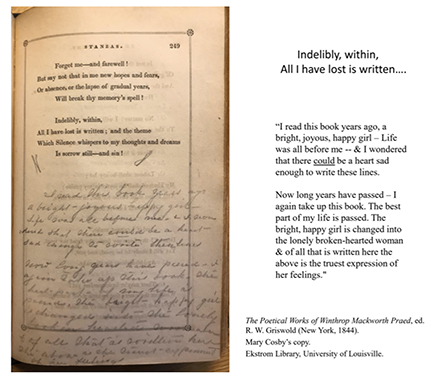

Stauffer heavily outlined the importance of book traces in his lecture, titled "Book Traces: 19th-Century Readers and the Future of the Library." Book traces often indicate the purpose or original use of literary works, he says, whether in an academic or casual setting. In addition, they enable readers to understand the social role or environment of the readers before them. In recording how and where a book once circulated, through names or other identifying markings, book traces may be utilized to map social networks between book owners and readers.

“I’m interested in the ‘traces’ in terms of that social-collaborative project: in what kind of information people are passing through the margins and annotations as a proto-social media space,” Licastro says.

“I’m interested in the ‘traces’ in terms of that social-collaborative project: in what kind of information people are passing through the margins and annotations as a proto-social media space,” Licastro says.

Knowledge of nineteenth century book marginalia has led Stauffer and Licastro, along with their students, to uncover some, otherwise largely unacknowledged, historical context. For instance, certain 19th-century books tend to have many annotations; this pattern provides insight into ones that were once curriculum, Stauffer says. During his lecture, he provided several examples of book traces that spoke to their original reader’s reception.

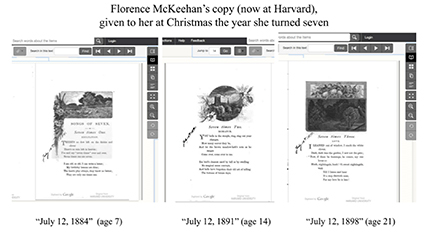

For example, the novel Songs of Seven is dated with the same day every seven years. This implies that it may have been used as some sort of birthday tradition. Other examples included conversations between two people, using the book as a communication forum, or showed books being used as diaries or mementos of a past self.

“My dream would be that whenever a book is touched, there is a trace protocol that it goes through,” Stauffer says. “The book would get a little mark on it or not, kind of like animal tagging, so that we can figure out what’s worth saving: either via the digitalization of marginalia or physical preservation.”

Nineteenth-century marginalia is far from rare. In fact, 12.5% of all pre-1923 monographs in circulating collections contain marginalia that can be “traced,” which means that Stauffer’s dream is possible.

Despite that promising fact, unfortunately, university and public libraries go through deaccessioning or book weeding processes that have yet to make tracking book traces part of the procedure. As a result, many of these books are taken off the shelves, in favor of newer, more modern copies.

“In the public library…we would take books out of the collection every five years and some of the basic criteria  was appearance, relevance, and popularity,” says Mallary Rawls, a Humanities Librarian with FSU Libraries. While this process looks different in academic libraries, books that are not checked out, or that have lost “relevance” over the years, are relocated, and their marginalia goes with them.

was appearance, relevance, and popularity,” says Mallary Rawls, a Humanities Librarian with FSU Libraries. While this process looks different in academic libraries, books that are not checked out, or that have lost “relevance” over the years, are relocated, and their marginalia goes with them.

“I can say with 100% certainty that more and more books, and their book traces, are going to be taken off the shelves because of space,” Licastro says. “As libraries modernize, students are not using the circulating stacks as much. [Deaccessioning] is happening all over the place and it’s only going to be exacerbated by the fact that the digital versions of these texts are getting more used.”

The Book Traces project and its discoveries serve as a reminder that physical collections have individual archival value. Rather than push back against digitization, Book Traces promotes the re-evaluation of the books that are deemed “valuable.”

“What we are saying is that in the circulating stacks there are books that are right on the cusp of being special or rare, particularly in the 19th century, that are at threat or risk,” Stauffer says.

Ultimately, Book Traces aims to raise awareness and to teach students to widely recognize marginalia as a historical artifact, and treasure it as such, via workshops, an online database, and book trace scavenger hunts—such as the one held at FSU’s Strozier Library on the same day as Stauffer’s talk.

For Licastro, Book Traces aspires to kill two birds with one stone.

“Let’s bring the students into the stacks and help the library through their deaccessioning process while simultaneously nurturing the student’s knowledge of marginalia,” she says.

Sydney Richner is an English major in the Literature, Media, and Culture Program with a minor in sociology. .

Follow the English department on Instagram @fsuenglish; on Facebook facebook.com/fsuenglishdepartment/; and Twitter, @fsu_englishdept