Judith Pascoe's extensive academic experiences shape the support she provides for her students

When Judith Pascoe arrived at Florida State University as a newly hired English professor, she knew right away how she wanted to collaborate with the department’s graduate student community. Pascoe asked to be a member of the job placement committee, because she wanted to help students prepare to navigate the post-degree environment.

Pascoe is aware that the tenure track job market is not as strong as it could be, and she believes “professors have an ethical obligation” to do what they can to help students find fulfilling work. She was fortunate, she says, to follow in the footsteps of the former placement committee director, English Professor Jamie Fumo, who had a strong program in place, and who shared all of the materials she had developed.

Pascoe came to FSU in the fall of 2017 from the University of Iowa, and she brought with her ideas behind the Next Generation Humanities Ph.D., a National Endowment  for the Humanities initiative that Iowa implemented during the 2016-17 academic year. Pascoe wrote the grant proposal for the project and was director for the program’s pilot year.

for the Humanities initiative that Iowa implemented during the 2016-17 academic year. Pascoe wrote the grant proposal for the project and was director for the program’s pilot year.

“We, as faculty, can empower our students by being supportive and by encouraging them to take the risk of doing something new, even if it is something we were not trained to do ourselves,” says Pascoe, who has served as director of the FSU English department’s placement committee. “We have to be less rigid about thinking we are duplicating ourselves in some way.”

Her proposal for the NEH grant was aimed at “reimagining Ph.D. training so that students are prepared for a greater variety of professions,” she says. The grant language, she explains, addressed rhetorical forms, ranging from traditional, long-form dissertations to the tweet, as a way to rethink the dissertation while enhancing students’ writing and technical skills.

The ultimate goal was for the graduate students to take charge of their educations, she says, and, in a way, to teach faculty members how to mentor them. Pascoe saw opportunities in the FSU English department to build on some of the experiences she had at Iowa. She also was ready for “a new challenge, to start fresh somewhere.”

“My graduate students at FSU have run with the concepts,” Pascoe says.

Alex Quinlan is pursuing a doctorate in poetry at FSU, and he is an advocate for the Next Generation Ph.D. philosophy—“I’m happy to sing Dr. Pascoe's praises,” he says.

“I appreciate her vigorous approach to her role as chair of the graduate student placement committee,” he says. He adds that he and other graduate students value Pascoe’s time during office hours. She consults with grad students on their application materials as they begin entering the job market, and she provides feedback on any documents the students bring in.

“She also is pragmatic, acknowledging that it is (as always) a tough market for us and encouraging us to look outside academe as we take the next steps in our professional lives,” Quinlan says. “Lastly, and perhaps most importantly, Dr. Pascoe expresses compassion for the vagaries of the academic job-search and a willingness to shape the committee's meetings to suit our needs. In short, she does an excellent job and I feel lucky to have her in my corner.”

During the summer of 2019, Pascoe is teaching at FSU’s Study Center in Florence, Italy, and she will be on a research leave during the spring of 2020. She is delighted that Associate Professor Tarez Graban, who will be taking over as the director of the placement committee, has designed a new placement practicum for the English Department. The course, ENG 5998-0002, begins in the fall of 2019 and is structured as “a cohort experience,” according to the course description.

More specifically, the course will be conducted as “a guided workshop, with the expectation that students come to the meeting each week with the draft or document we are working on for that day, giving everyone plenty of opportunities to offer and receive feedback on the essential genres.”

“I think we have to try even harder to make sure that students are equipped with rhetorical skills to write about what they are doing in a way that will make them compelling candidates for a broad range of jobs,” says Pascoe. “We also need to see that students who want to take career paths outside of academia feel supported and encouraged.”

That notion of support is one of the reasons why Pascoe chose to come to FSU after spending 24 years at Iowa. During a job talk in front of her soon-to-be colleagues, she appreciated learning about how the three main English department programs are integrated and influence one another. Another detail that helped with her final decision is that the FSU faculty is unionized.

“I heard that and felt like it’s a sign that the faculty and the administration work together in a collaborative way and make sure that everyone has good working conditions,” she says. “This institution has its heart in the right place. There seems to be strong guidance at the dean level and provost level, and people work together toward common goals.”

Pascoe was hired as the George Mills Harper Professor of English. Harper, she explains, was a scholar of William Blake and W.B. Yeats, and he also was a beloved teacher. That last part motivates Pascoe as a member of the English department.

“I love my students here,” she says. “I’ve had great experiences with teaching, on both the undergraduate and graduate level.”

FSU, she says, has given her a new lease on life in terms of teaching. One specific course she enjoyed was British Romanticism, because she worked in conjunction with Strozier Library staff members, who allowed students to experiment with computational analysis, mapping, and text encoding.

Sarah Stanley, a digital humanities librarian in Strozier, has facilitated instruction sessions for Pascoe and her class. They worked on a text analysis assignment, and Stanley taught the students how to use the web-based tool Voyant for the process.

“Even when teaching challenging new methods, like text analysis and digital mapping, Dr. Pascoe makes space in her classroom for her students to pursue new methods of inquiry,” Stanley says. “Every time I have the opportunity to work with her, I am reminded of her investment in supporting students as they develop their scholarly identities.”

Pascoe is working with Stanley, Associate Professor Graban, and Dr. Allen Romano, the coordinator of the Digital Humanities Graduate Program, on the Demos Project, an initiative aimed at creating a research/training space and community hub for humanities data analysis and curation. The planned Demos Center for Studies in the Data Humanities will provide fellowship opportunities for graduate students.

As much as Pascoe enjoys working with students, she also appreciates working with her colleagues. She became involved in the hiring process for the three English department members who were hired in Fall 2018, Lindsey Eckert, Jaclyn Fiscus, and Frances Tran.

“The hiring process gave me insights into how the different programs are run and how they might interact with each other,” Pascoe says. “Of course, I had my own experience the year before as an interviewee, and this time I saw the other side of the process.”

During the job talks, aspiring faculty members talk about their research and publications, areas where Pascoe stood out to her department colleagues. She has published four books, including her two most recent ones, The Sarah Siddons Audio Files: Romanticism and the Lost Voice in 2011, and On the Bullet Train with Emily Brontë: Wuthering Heights in Japan in 2017.

During the job talks, aspiring faculty members talk about their research and publications, areas where Pascoe stood out to her department colleagues. She has published four books, including her two most recent ones, The Sarah Siddons Audio Files: Romanticism and the Lost Voice in 2011, and On the Bullet Train with Emily Brontë: Wuthering Heights in Japan in 2017.

In graduate school, first at Syracuse University, where she earned her master’s degree, and then at the University of Pennsylvania, where she earned her doctorate, Pascoe recognized that scholars were beginning to challenge the traditional British Romantic canon, which, she says, revolved around a half dozen male writers.

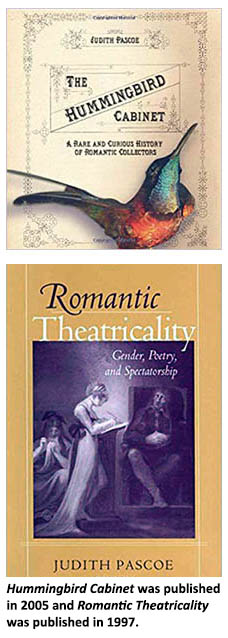

She focused on British women writers, such as the poet Mary Robinson, one of the main subjects of her first book, Romantic Theatricality: Gender, Poetry, and Spectatorship. Pascoe says she wanted to give attention to a genre that had been overshadowed, so she focused on how poets used theatrical strategies to fashion their self-representations.

That line of inquiry sparked Pascoe’s interest in Sarah Siddons, arguably the most famous actor of the Romantic period, Pascoe says. She wanted to understand why she was so admired.

“I developed a hypothesis that it had to do with the quality of her voice,” Pascoe says.

Researchers and scholars could not access recordings of Siddons, since there was no such technology during her career, which spanned from 1774 to 1812. People instead focused on images of Siddons, how she looked, how she performed, her gestures, Pascoe says. But she wanted to “hear” this person who was never recorded.

“As it turned out, she was recorded in some ways,” Pascoe points out. “One fan sat in the audience and took notations in the margins of copies of the plays in which Siddons performed, and so provided some hints of what was so powerful about her voice.”

Those historical musings about Siddons’ voice have broadened Pascoe’s perspective, and she wonders if the advent of sound technology has led us to listen differently.

“If you can record everything, you might not feel compelled to listen as closely to the voice,” she says.

After that dive into cultural history, Pascoe says she wanted to focus more on literary analysis. She had received a Fulbright Lecturing Award for the 2009-10 academic year, and she went to Japan to teach American literature. One of her classes read The Scarlet Letter over the course of an entire semester, while her other class studied Death of a Salesman and The Glass Menagerie.

During her time in Japan, Pascoe had a copy of Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights with her. Her idea was to start a new research project based on the book, but she says she wanted to avoid doing what she typically does with a project, “which is go off in a million different directions and think about the cultural history and other issues.”

“When I got to Japan, I found out Wuthering Heights is really popular there—people are oddly familiar with the novel,” Pascoe says.

Translated into Japanese, the title Wuthering Heights is Arashi ga oka, and there are roughly 20 translations of the novel into Japanese. Pascoe wondered why there would be so many different versions of a Western literary work. She started to collect translations and adaptations, everything from theater productions to Japanese film versions.

“On the Bullet Train with Emily Brontë is about the Japanese versions of the novel, but also about changing notions of intellectual mastery,” Pascoe says. “We’re in a different culture now with so much information accessible, and the kinds of ways we used to think we had to memorize things may not be as relevant.”

What started out as Pascoe initially wanting to focus on fully learning Wuthering Heights morphed into her wanting to learn Japanese so that she could understand the translated versions.

“So, there begins the sad, tragic story of my ten years of attempting to master Japanese,” she says. “I was—and am—always studying kanji, and there are 50,000 of them, 2,000 of which are in common use. You need to be able to read 2,000 kanji to read the newspaper.” Pascoe says she would learn them and forget them, learn them and forget them.

Pascoe went through four years of undergraduate studies at Iowa in Japanese. “Taking those classes was transformative,” she says. “If you’re the kind of person who becomes an academic, you’re used to being a good student. You just think, ‘Oh, if I work really hard, I’ll get good grades.’

“But if you are thrust into a language class with 18- to 20-year-olds when you’re older, you are likely going to be the slowest person in the room, no matter how much you rely on your good study habits.”

Since she has been at FSU, with help from four FSU undergraduate students in the UROP program, and in collaboration with Matt Hunter, Strozier Library’s digital scholarship technologist, Pascoe has expanded her book. They have created a Zotero database to put together data and bring together both Japanese and English citations of Wuthering Heights adaptations, creating metadata so that others can use the research.

With the students in her FSU classes, she emphasizes the notion that curiosity is an important characteristic to call upon when it comes to research. For example, when one undergraduate class was working on 19th-century serial novels, Pascoe sent the students in small groups to the library and told them to look at the wall of books about Thomas Hardy.

“They do everything electronically now, but there is a serendipity to having shelves and shelves of library books in front of you,” she says.

Each group assigned topics to themselves, and they ended up with categories such as the biography group and the contemporary reviews group, to name two. She encouraged the students to pick up books about their specific topics.

“Even more importantly, though, I wanted them to take books that looked interesting to them, and if that swerved them into different directions, that was fine,” Pascoe says.

She had that similar experience with her journey from pursuing research into Wuthering Heights to discovering the Japanese translations to studying Japanese. Her time spent learning Japanese made her feel a solidarity with students who fear getting called on by a professor and being unable to come up with a correct response.

“In some ways, it was a humbling experience,” Pascoe says. “But being a bad student in Japanese has had good impacts on the way I view my students.”

And for Pascoe, that point of view brings her back to how she strives to help her students, undergraduate or graduate, both in the classroom and as they move into their professional lives.