In the summer of 1967, The Beatles released "All You Need is Love," a song with a simple message of peace and unity. A little less than 10 years later, in the spring of 1977, the Sex Pistols thrashed the airwaves with their most-acclaimed single, "God Save the Queen," with lyrics that include the repeated ending, "No future / no future for you / No future for me."

In the summer of 1967, The Beatles released "All You Need is Love," a song with a simple message of peace and unity. A little less than 10 years later, in the spring of 1977, the Sex Pistols thrashed the airwaves with their most-acclaimed single, "God Save the Queen," with lyrics that include the repeated ending, "No future / no future for you / No future for me."

Based on not only those small samples, but also on their discographies—granted the Sex Pistols have just one studio album to their credit—some could easily make a case that the Fab Four and Johnny Rotten and his mates have very little in common. "You do not normally try to put the Sex Pistols and the Beatles together," Barry Faulk says.

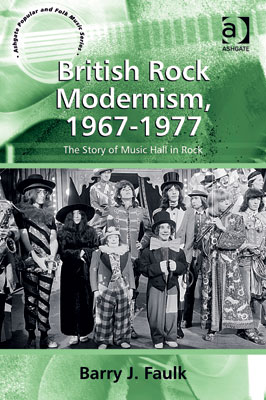

Yet, in his recent publication, British Rock Modernism, 1967-1977: The Story of Music Hall in Rock (Ashgate, 2010), Faulk argues that these and other British rock bands of the era are engaging the same historical tradition of British music hall.

Yet, in his recent publication, British Rock Modernism, 1967-1977: The Story of Music Hall in Rock (Ashgate, 2010), Faulk argues that these and other British rock bands of the era are engaging the same historical tradition of British music hall.

"British rock is about the passion of post-WWII Britons for American music, most of it Southern and African-American," Faulk says. "It's a complicated mix of admiration, imitation, and creative 'borrowing.'

"British rock bands were often also enthusiastic record collectors, not to mention music purists, who tried to champion their specialized tastes to a mass American audience," Faulk continues. "In this context, the persistent, obviously English, strains of music hall in rock bands like the Kinks and the Beatles is puzzling: or at least it puzzled me as an American fan of these bands."

In British Rock Modernism, 1967-1977, Faulk argues that "the music hall component of British rock was an attempt by musicians to make sense of their own history, as well a way to assert the new art status of rock. It's that last point about artistic pretensions—I mean that in a good way—that links rock to modernism."

"Talking about rock, in other words, permits me to talk about a lot of other things: gender, performance, history, modernism, etc."

According to the publisher's website, Faulk's book examines recordings such as the Beatles' "Magical Mystery Tour" album, "The Kinks are The Village Green Preservation Society," and the Sex Pistols' "Never Mind the Bollocks: Here's the Sex Pistols," as well as television films such as the Beatles' "Magical Mystery Tour" and "The Rolling Stones Rock and Roll Circus," projects that defined rock's early high art moment.

"The book has been well received by modernist scholars I know," Faulk says. "This is partly because they recognize what I'm doing, since there's much current research on the modernist legacy in contemporary culture."

Faulk is also writing a blog, called "Brit Rock Modernism," where he discusses music-related issues and posts on topics related to his current publication, and his next project as well. For that he is writing an article that expands on the 70s chapter in British Rock Modernism, 1967-1977.

"I discuss a musical phenomenon particular to the early 70s, when a score of rock groups from Slade to Ian Dury and the Blockheads incorporated music hall style," Faulk says. "I argue this trend amounted to a critique of the still recent idea of art rock."

Faulk sees that essay as part of a larger research project about changing performance styles in the British 70s.

"There were various efforts to redefine theatre and performance in the late 60s and 70s, with a mind to politicizing audiences and spectatorship," Faulk says. "My project will discuss rock groups like the Who and Pink Floyd, but also performance artists like Gilbert and George, who began their art career as postmodern vaudevillians, as well as the Moodies, a women's vocal group that blurred the lines between rock, theater, and performance art."