The travels of Kelly Hall, from the highs of academia at FSU to the bottom of the world

By Tatia Ghviniashvili

The travel bug bit Kelly Hall at the age of 14, when she traveled to both England and France for a high school trip—forever changing her life.

“It was a gateway drug,” says Hall, a Florida State alumna with her doctorate in Literature. “I couldn’t wait to go back.”

Hall was never handed anything in her life. She worked hard for every achievement, seeking opportunities in education and travel everywhere she went. In addition to traveling at a young age to Europe,  Hall has seen—and done—a lot. She has even worked in Antarctica, for the United States Antarctic Program.

Hall has seen—and done—a lot. She has even worked in Antarctica, for the United States Antarctic Program.

Hall successfully completed her Ph.D. in 2016 and her dissertation was entitled, “Seeing the Self: Personal Motivation in Late-Medieval British Travel Accounts.” Hall was recently hired as the Director of Global Initiatives and International Programs at Cedar Crest College in Allentown, Pennsylvania. Hall says that her position is geared toward helping students travel abroad.

Hall’s hard work and passion during her academic and professional journey from FSU to Cedar Crest College has led her to where she is in life. She says it is important for current and prospective students to know just how much opportunity there is in this world, and Hall’s life is the perfect example of that.

The voyage began for Hall in Buckhannon, West Virginia, a small college town with only about 5,500 people. Her mother—a high school French teacher then, and an elementary principal before she retired—often took trips to Europe with her students, largely contributing to Hall’s love of travel.

“Her stories, and the unique gifts she brought home, got me interested in international travel at a young age,” Hall says about the inspiration her mother had on her.

Clearly in love with travel, Hall was careful in selecting her college once out of high school, one where she could have opportunities to study abroad. And not just study abroad, but actually learn about her environment. For example, when she studied at a French university, she lived with a host family and became completely submerged in the culture.

“I chose Sweet Briar College for my [Bachelor of Arts] because they had been running an intensive and well-respected study-abroad program for France for almost 50 years,” Hall says.

Soon after finishing her undergraduate studies, Hall began eyeing Master of Arts programs, and she eventually decided to pursue her graduate degree at the University of York in the United Kingdom. Hall started out as a history student but soon converted to medieval studies. That switch prompted her to pursue a doctorate degree in Medieval Literature at FSU.

While at FSU, Hall worked closely with faculty members, including English Professor David Johnson, who referred to her becoming a medieval literature convert as “coming to the dark side.” Hall talks fondly of Johnson, calling him her hero.

“He was always very supportive—not only of my academic endeavors, but also my personal ones,” Hall says. “He wrote recommendations which helped me win a dissertation research grant and a teaching award. Most importantly, he allowed me to take time to scratch my travel itch, whether that was being a professor for the United States Navy or going to Antarctica.”

Johnson says when he learned a student with an M.A. from York was joining FSU’s English doctoral program, he knew the student would be well prepared, considering York’s academic reputation.

“Boy, was I right—Kelly was an excellent student: curious, dedicated, talented,” Johnson says. “She does have a wandering soul, as witnessed by her extensive travels, but I take pride in having been able to steer her definitively toward medieval literature. Due to the number of tools a Ph.D. student in medieval studies must acquire—languages, languages, languages—as well as the full teaching load our students are saddled with, it is not unusual for a student studying medieval literature to need more time to finish than the financial package they receive from us can provide.”

Johnson points out that Hall did not panic at the challenges she faced. Instead, he says, “she spent entire semesters working on Navy ships teaching sailors while traveling the world, and added several stints in Antarctica just for good measure.”

“Kelly wrote a dissertation to be proud of, and while it may have taken her longer than she might have wished, nothing, and I do mean nothing, was going to keep her from doing just that: she finished in style, and now has her dream job,” Johnson adds, emphasizing her accomplishments.

Along with Johnson, Hall fondly reminisces on other professors, such as Marcy North (now at Penn State University) and Nancy Warren (at Texas A&M University), saying both were instrumental in her education.

“Both are top-notch professors who mentor and support other female academics,” Hall says. “I learned so much from each of them—whether in the classroom or while writing.”

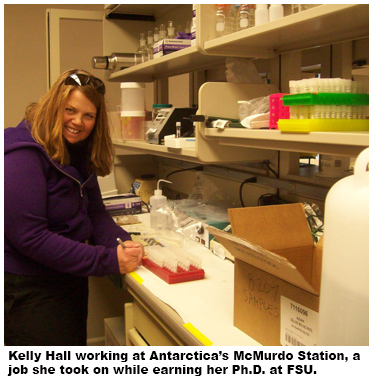

Not many students get to say they worked for the United States Antarctic Program, while in pursuit of a Ph.D.—an impressive achievement for Hall and one that could inspire students she currently works with to boldly take risks in life, both academically and professionally.

Being selected to work in Antarctica for the United States Government is no easy task, considering the application pool can allegedly reach 30,000 and only 1,000 are selected. Hall did not let these odds stop her from applying multiple times until finally, on the third try, she was given the opportunity she had been waiting for.

So, this was Hall’s life now: she was a PhD student; working on her education, while at the same time working at McMurdo Station, which is on the south tip of Ross Island.

“My first job on ‘The Ice’ was as a vehicle operator,” Hall says. “I learned how to drive large, articulated vehicles called deltas, and everyone’s favorite form of transport, the much-loved Ivan the Terra Bus,” a specialized passenger transport vehicle.

“My first job on ‘The Ice’ was as a vehicle operator,” Hall says. “I learned how to drive large, articulated vehicles called deltas, and everyone’s favorite form of transport, the much-loved Ivan the Terra Bus,” a specialized passenger transport vehicle.

Hall has been to Antarctica four times, always in the busier summer season, which is October through February. The population of McMurdo Station grows to about 1000, five times the number who live there in winter. Hall’s main job on the ice was transporting people back and forth between the station and the airstrip. On Hall’s most recent trip to Antarctica, her job was handling the logistics and cargo coordination for a deep-field camp.

“My favorite thing about working at McMurdo Station was the people, and I made lifelong friends there,” Hall says. “They represent an amazing range of ages, experience, and skill sets. People there are gay and straight, young and old—one fellow driver was 81—married and single, first-timers and old-timers.

“One running joke is that there are more Ph.D.s working in the cafeteria than there are in the science lab.”

Hall talks about how no matter the background of each employee, everyone’s skillset was always useful in some way or another, making McMurdo Station an egalitarian society.

“Many of my friends were computer nerds—I say that with the highest respect—and they were always helping me with my tech issues,” Hall says. “But my liberal arts skills were valued too. I translated for French visitors, and I edited several friends’ résumés and cover letters.”

Hall also talks about the unique opportunities she had while working in Antarctica. Not that being in Antarctica in the first place is ordinary. For example, Hall was a chauffeur to Prince Albert of Monaco, and she also chatted with Sir David Attenborough at a party sponsored by the BBC.

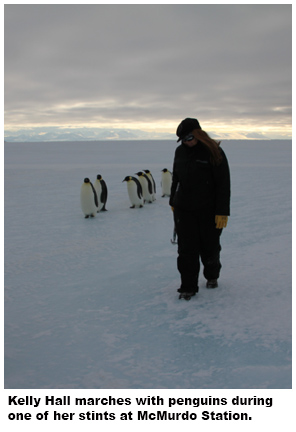

Plus, how many Ph.D. students get to say they “literally marched with penguins” in Antarctica? In some circles, that’s an impressive asset to anyone’s résumé.

Hall’s travel experience does not end there, though. When Hall was ready to find a career off “The Ice,” she settled at Cedar Crest, which allows her to travel and help eager students do the same.

Hall’s travel experience does not end there, though. When Hall was ready to find a career off “The Ice,” she settled at Cedar Crest, which allows her to travel and help eager students do the same.

“I work with the college’s international partnerships and faculty-led study tours, but one of my central tasks is directing the Sophomore Year Expedition,” she says. “This is a unique program, unlike study abroad opportunities offered by other colleges. It is a free, guaranteed trip for sophomores in good standing.” Students only have to pay for their passports.

The travel abroad program at Cedar Crest began two years ago, before Hall was hired in early 2019. Students have traveled in the past to Rio de Janeiro, and this year to Athens, Greece, helping to internationalize the campus and promote global learning. The program focuses on experiential learning along with academic coursework, with students working and learning alongside local populations.

“As we say at Cedar Crest, we’re going ‘for the people, not just the place,’” she says. “My hope is that our students will come away with a greater understanding of, and appreciation for, different perspectives.”

Hall clearly has pure enthusiasm for travel and a desire to learn about the world—all of its nooks and crannies. The way Hall talks about her experience shows what it means to become dedicated to and enthralled in something. Her story is a testament to both learners and explorers.

And if you can, her adventures show, travel to broaden your mind and global awareness. The advice Hall passes on to current and prospective students at her alma mater is simple: “Go traveling! Study abroad! Teach abroad! Work abroad!”

Tatia Ghviniashvili is a senior who is majoring in English, with a concentration in editing, writing, and media, with a minor in Russian language.