Anthony Cormier's move to Tallahassee and FSU was a big step toward life-changing experiences

By Faith Matson

As many stories do, this one started with a love interest.

Anthony Cormier, a 2000 graduate of Florida State University’s Creative Writing Program, moved to Tallahassee as a transfer student from the University of Florida to follow a girl.

While his move to FSU, the place that would provide a foundation for a prolific writing career, was somewhat spontaneous, his success that would follow proves that not all rash decisions end badly.

In 2016, Cormier became a Pulitzer Prize-winning investigative reporter.

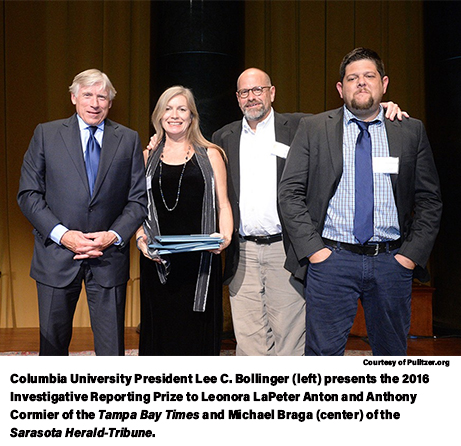

While working for the Tampa Bay Times, Cormier, in collaboration with two other journalists from the Tampa Bay area, earned the Pulitzer Prize in Investigative Reporting for a series of articles called “Insane. Invisible. In danger.” The five-part series covered many of the dangerous incidents that were occurring at Florida mental institutions due to budget cuts.

Earlier this year, Cormier was recognized as a finalist for the 2021 Pulitzer Prize in International Reporting for his work on the FinCEN Files Series, a series of articles from Buzzfeed News that exposed criminal activity in banks around the world.

Since his graduation from FSU, Cormier has managed to go from a young father working night shifts at a loading dock to a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist – just how he achieved such success is quite a story.

Since his graduation from FSU, Cormier has managed to go from a young father working night shifts at a loading dock to a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist – just how he achieved such success is quite a story.

Florida State University

Cormier laughs as he explains his move from Gainesville to Tallahassee.

“I think it was a little bit of a unique college experience because the girl I went to see, I ended up getting pregnant,” he says.

This was his freshman year.

Fatherhood forced Cormier to mature quickly, and though he might have expressed interest in a few other areas of study, writing satisfied his needs at the time. Because he had to work to support his family, he was able to come home late at night and read or write for his classes without feeling the task was too arduous.

“My memories are having a little one in my lap, my wife having a class on one side of campus, me having a class shortly after that, and us having to pass off a baby,” Cormier recalls. “I didn't have the typical college experience in any measurable way.”

Luckily, Cormier encountered a professor at FSU who made a profound impact on his studies. After taking a class with Mark Winegardner, Burroway Professor of English at FSU, Cormier felt greater confidence in his decision to pursue a writing career.

“I just found him to be a really special professor,” Cormier explains. “I thought his writing was brilliant, obviously. I thought he seemed to care about everybody in the class, and care about us a little bit beyond the sort of instructional side.”

Cormier notes that Winegardner knew of his “situation” – i.e., needing to care for a young child – but still maintained a consistent sense of professionalism with Cormier. He wasn’t allowed to turn in late work just because he worked the night shift, and Cormier appreciated the accountability.

"He just was the kind of professor who took a bunch of kids who thought they were gonna write the, you know, ‘the Great American Novel’ and help them believe that they could,” Cormier says. “He didn’t play favorites…he just helped you become a better writer to the best of your ability and I was always so grateful for that.”

When I first met Anthony, he was going through some challenging things in his personal life. As a writer, he was raw, but the talent and the doggedness were both there.

— Mark Winegardner

Winegardner distinctly remembers his time working with Cormier.

“When I first met Anthony, he was going through some challenging things in his personal life,” Winegardner explains, remembering how Cormier appeared to be at a crossroads of youth and adulthood while awaiting the arrival of his daughter. “As a writer, he was raw, but the talent and the doggedness were both there.”

Winegardner emphasizes that Cormier already possessed the desire and work ethic that can’t be taught in a classroom.

“Anthony loved muscular and tender-hearted writing, but he also loved the hard work it takes to create work that reads as if it came easily,” he says.

Early Career

After graduating from FSU, Cormier and his then-wife moved to Panama City, Florida, so she could attend FSU’s graduate program for behavioral psychology.

“I don't know if you've been to Panama City—no offense—it's not a teeming metropolis,” Cormier says, with a chuckle. “It’s not the land of plenty where a young person with a degree can go and get an immediate white-collar job.”

Cormier continued to support his family however he could, but he struggled to find a writing job. While working some other jobs, though, Cormier tried to land a position at the Panama City News Herald.

“I talked to their managing editor at the time, and I was like, ‘Look, I'm a pretty good writer, here's my stuff, sign me up coach,’” Cormier explains. “And he was basically like, ‘You're not good enough.’”

Though Cormier was denied a job in the newsroom, he was offered a job on the loading dock bagging newspapers for delivery. After finishing his bartending shift working at O’Charley’s, a restaurant in town, at midnight, he would head to the News Herald’s back lot and bag newspapers, load them into his car, and deliver them until 3 or 4 in the morning.

“I just thought, ‘I don't know how to get my foot in the door of journalism, but hey, I'm here, I'm at the building,’” Cormier says. After a stint delivering newspapers (badly, Cormier admits), the News Herald’s sports editor called him and offered him a freelance assignment.

The article involved interviewing a local musician, which sent Cormier to a jazz show.

“I wrote in the lead that the crowd was awash in Members Only jackets, which was a very on-brand kind of thing,” Cormier explains, remembering the club’s environment.

The detail impressed his editor, and he asked Cormier to apply for a full-time sports writing position. Cormier did, and he got the job, but he struggled initially.

“And I almost immediately got fired because I kept [screwing] up names,” Cormier says. “I couldn’t get the names spelled right.”

Because he lacked journalistic experience, Cormier wasn’t accustomed to the precision the job required. His editor explained the necessity of ensuring names were spelled properly for the sake of not only the articles’ subjects but also for their family members.

“He was like, ‘Look, Grandma is going to clip out this little paragraph. This little brief that you're writing needs to be the best, most accurate, perfect thing you've ever done,’” Cormier says.

He did not get fired, but Cormier took away a lesson in gaining audience trust that has remained with him throughout his career.

“If we’re screwing up on the little things, are we gonna screw up on the big things?” he posits.

After completing his time at the News Herald, Cormier moved to write for the Sarasota Herald-Tribune.

“It had this reputation for being a very punch-above-your-weight investigator job,” Cormier says, explaining his reason for moving from the Florida Panhandle to the state’s central Gulf coast. “And I was really keen to learn about how to do that type or reporting.”

An Award-Winning Journalist

Cormier spent some time at the Herald Tribune before making the move in 2015 to the Tampa Bay Times, where he would continue work on a project he and Herald Tribune colleague Michael Braga had begun before Cormier’s move.

His former colleagues had accumulated a large set of data on Florida’s mental institutions, although none of them could seemingly make sense of the information. Essentially, the data tracked all of the arrests made in the state of Florida over a lengthy period of time.

“They track everything from their initial arrest all the way through their prosecution, and the outcome, and any appeals,” Cormier explains.

No one knew quite what to do with the data, Cormier says. They scrutinized the materials for differences based on race, gender, and class, but they then noticed an interesting category of people on the spreadsheet and decided to look further.

“They're appearing in this field, but then they're in prison for a really long time for minor offenses, [such as] shoplifting, and they were seeming to be in custody for a decade,” Cormier says. “What the hell happened here?”

The journalists soon learned that the state deemed these people to be incompetent and mentally unfit to be charged with a crime, as they either did not understand that their actions were criminal or would not understand the trial proceedings.

“They had basically been warehoused in these jails in the interim [before going] to one of these state-run hospitals,” Cormier elaborates. “And that's basically what all journalism is: you just come up on something and be like, ‘so what's the story here? What's going on here?’”

Cormier and Braga felt compelled to dive deeper, bringing on Cormier’s Times colleague Leonora LaPeter Anton for the process. When the trio started, they believed the warehousing of mentally incompetent people in jails was the extent of the story. They had no idea, though, that they were uncovering massive shortcomings within Florida mental institutions.

“The much larger story is that the violence inside these places has increased dramatically because the state of Florida has quietly stripped their budgets, leaving less people to care for the most vulnerable, the most dangerous, the folks who need the most,” Cormier says.

After the publication of their multi-article series, which delved into the short-staffing and mistreatment within the institutions, the state of Florida responded, reallocating funds toward the improvement of the conditions for both patients and workers at the institutions.

“It was just a remarkable thing that the legislature undertook, and I was really grateful that somebody had read the stories and decided to act,” Cormier says. “Because we had met staff members and patients who really do care and want to do a better job…and were frankly delighted to have more help.”

“It was just a remarkable thing that the legislature undertook, and I was really grateful that somebody had read the stories and decided to act,” Cormier says. “Because we had met staff members and patients who really do care and want to do a better job…and were frankly delighted to have more help.”

When he and his coauthors received the 2016 Pulitzer Prize in Investigative Reporting for the work, though, Cormier says he was completely surprised.

“You start out on the loading docks of the Panama City News Herald with a kid and multiple jobs, you just don't – that's just not in the cards,” Cormier explains, noting that he still feels a sense of disbelief.

Winegardner, Cormier’s former professor, remarks how difficult it is for someone who did not attend a specialized private school or work with a major organization to get a job at a reputable paper.

“It takes a lot of grit to go from someone who learned to be a journalist at small, obscure newspapers struggling to stay afloat and even get a job at place like the Tampa Bay Times,” Winegardner says about his former student. “But he just kept rising, becoming a key part of a team that won the Pulitzer and distinguishing himself there and at BuzzFeed as a heavy hitter in the evidence-based unveiling of some of the most dangerous criminals in American political history.”

Humble by nature, Cormier doesn’t like to boast about the Prize, and for him, it doesn’t change much about his work.

“For a long time, the Pulitzer was in a closet, I didn’t really think about it because you have to keep doing it,” he says. “So it’s nice, but cool, move on.”

At Present

In early 2017, Cormier changed jobs again, this time to Buzzfeed News, where he currently works as an investigative reporter. During the first four years of his job, he spent the majority of his time investigating former President Trump’s administration.

“That meant debunking stories about the president and his friends and colleagues, and sometimes it meant looking into some of the more important things that he had done,” Cormier explains. “It's been so polarized, like that whole four years is now kind of a blur.”

Now at a national news organization, Cormier remarks on the intense public scrutiny he’s received in his new position.

“It was just so polarized, there was nothing you could do to cut through that without half the people thinking you're some kind of resistance hero—which I am not—and half the people thinking I'm some kind of fake news jerk who's trying to take on the president,” he says.

Despite the weight of his new role, Cormier’s achievements have continued to follow him. Earlier this year, the Pulitzer Prize board recognized him and 10 Buzzfeed colleagues as a finalist for the 2021 Pulitzer Prize for their work on the FinCEN Files Series, which exposes corruption within the global banking industry.

“The FinCEN Files were thousands of unprecedented records that showed how the biggest banks in the world were facilitating some of the  worst atrocities,” Cormier says. “They were basically banking Narcos, and terrorists, and they knew it…and the U.S. government did nothing about it.”

worst atrocities,” Cormier says. “They were basically banking Narcos, and terrorists, and they knew it…and the U.S. government did nothing about it.”

The creation of the FinCEN Files required a vast, worldwide collaboration of journalists.

“We worked with a group of journalists in 108 countries, and we all published stories from our various jurisdictions…hundreds and hundreds of stories about national misconduct the world over,” Cormier explains. “And they had an immediate impact.”

Officials all over the world began making institutional changes after the FinCEN Files Series was published, weeding out the criminals who moved money through their banking systems.

Jason Leopold, who worked with Cormier on the FinCEN Files Series, has high praise for his ongoing collaborator and their many projects together.

“Anthony and I have so many greatest hits that we released over the past four years under the double byline of 'Cormier-Leopold/Leopold-Cormier' that I sometimes joked with him that my next one is going to be a solo album,” Leopold remarks.

He adds that he could never imagine working with anyone else in the same way.

“Simply put, Anthony is fearless. There is nothing that will stand in his way of trying to uncover the truth,” Leopold says. “I count myself incredibly fortunate to work with him. Every single day is an adventure.”

Active FSU Alumnus

Cormier has remained involved in the FSU community. His daughter recently graduated from her parents’ alma mater with a degree in behavioral psychology – the same degree as her mother.

Cormier also gave a TEDTalk at the university in 2017, which taught students how to seek out unbiased information in the modern era. His main takeaway from the TEDTalk, though, is something unexpected:

“I should’ve worn a suit,” he says with a laugh. “I was glad to have done it, should’ve worn a suit.”

As for having any role in Cormier’s success, his former professor takes no credit.

“All teachers who've been fortunate enough to mentor a few students who go on to make it big know the truth of that old saying – ‘when the student is ready, the teacher will arrive,’” Winegardner explains. “All we really did was show up.”

As for how he uses his degree in creative writing, Cormier believes the lessons he learned helped him pay attention to minute details. In his interviews, for example, he’s often able to notice whether someone is nervous or hiding something.

“It's that kind of eye that you might use as a novelist but you also need to use as an investigator,” he says.

And despite his success, Cormier has no plans of slowing down.

“You’re only as good as your last one,” Cormier says, referencing his countless projects. “And that one’s over, so what’s my next one?”

The FSU community is looking forward to finding out.

Faith Matson graduated at the end of the summer 2021 term as an English major on the editing, writing, and media track. She is also pursuing a certificate in Global Citizenship.

Follow the English department on Instagram @fsuenglish; on Facebook facebook.com/fsuenglishdepartment/; and Twitter, @fsu_englishdept