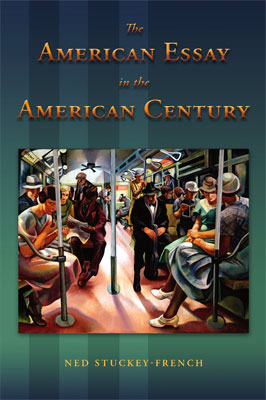

In his new book, The American Essay in the American Century (U of Missouri P, 2011), Ned Stuckey-French offers not only a cultural history of the personal essay but also a defense of that oft-neglected art form.

In his new book, The American Essay in the American Century (U of Missouri P, 2011), Ned Stuckey-French offers not only a cultural history of the personal essay but also a defense of that oft-neglected art form.

Since the 1890s, American critics have debated the "the death of the essay." Even now, the personal essay continues to be seen as a service genre—one that is used to write about other more "literary" genres, one that is used to teach young people how to write, one that is considered the "fourth genre."

While a graduate student at the University of Iowa, Stuckey-French focused on the personal essay and participated in a study group organized by Carl Klaus, an American essay scholar. The group amassed an archive of writing by practicing essayists, starting with Montaigne, in which those writers discussed the art of the essay.

"The archive of material we uncovered proved to be rich and especially so for America during the first half of the twentieth century," Stuckey-French says in an interview at his publisher's site. It introduced him to writers such as Heywood Broun, Alexander Woollcott, Dorothy Parker, and Christopher Morley, who "revolutionized the American essay" by creating "a new kind of essay that was street-smart, witty, irreverent, political, and hip, and decidedly not genteel."

The debate over the supposed demise of the essay provided a narrative thread to his book, says Stuckey-French, but he adds that increasingly he "saw that the book was also about the development of America's new middle class during this period. That class, which John and Barbara Ehrenreich have called the 'professional-managerial class,' or PMC, constituted the readers of these essays and the magazines in which they appeared." The American Essay in the American Century "came to be not just about the essay as a fireside chat, but also about Franklin Roosevelt's fireside chats as essays. It came to be about not just E. B. White as a New Yorker humorist and the author of Charlotte's Web and Stuart Little, but also E. B. White as a committed liberal and Thoreauvian who battled fascism in the columns that became One Man's Meat."

The debate over the supposed demise of the essay provided a narrative thread to his book, says Stuckey-French, but he adds that increasingly he "saw that the book was also about the development of America's new middle class during this period. That class, which John and Barbara Ehrenreich have called the 'professional-managerial class,' or PMC, constituted the readers of these essays and the magazines in which they appeared." The American Essay in the American Century "came to be not just about the essay as a fireside chat, but also about Franklin Roosevelt's fireside chats as essays. It came to be about not just E. B. White as a New Yorker humorist and the author of Charlotte's Web and Stuart Little, but also E. B. White as a committed liberal and Thoreauvian who battled fascism in the columns that became One Man's Meat."

Alan Nadel, author of Containment Culture and Television in Black-and-White America: Race and National Identity, adds, "Always insightfully attuned to the cultural politics negotiated by the American essayist as he or she constructs ideal readers and idealizes the authorial position from which to address them, Ned Stuckey-French deftly examines the history of the essay in American culture. This is a smart, artful discussion of an important American art form."

The work that Stuckey-French began at Iowa has led to a collection of essays titled Essayists on the Essay: Montaigne to Our Time (forthcoming U of Iowa Press, March 2012), which he co-edited with Carl Klaus. The volume's contributors represent four centuries and several countries including Mexico, Argentina, Venezuela, Spain, Switzerland, France, Germany, Australia, and Canada as well as England and the United States. Several of the pieces are translated into English for the first time. They include discussions of the essay's relationship to other genres, its common tropes, its evolution as a form, and what the digital age might hold for its future. The book includes a comprehensive introduction, biographical head notes, an index, and a bibliography of more than 200 entries.

Robert Atwan, editor of the Best American Essays series, wrote in his reader's report that "Carl Klaus and Ned Stuckey-French are among the finest commentators on the genre today. Their presentation of the material is compelling and in my opinion the project when published will surely be extremely valuable to all of us—we teachers, writers, critics, and educated readers who remain devoted to furthering the study of the essay."

Other upcoming projects will take Stuckey-French further into both the essay and middlebrow culture. He has organized a conference panel on digitization and the essay, published an article on Facebook and the essay, and has a review-essay about video essays forthcoming in the American Book Review. With the help of several graduate students and a grant from the Florida State University Council on Research and Creativity, he is assembling a digital archive of American essays. This archive will include (while respecting the "fair use" provision of copyright law) scans of essays as they first appeared in magazines as well as a sampling of surrounding ads, articles, and illustrations, contributors' notes, tables of contents, subsequent letters to the editor, and other materials that might help inform readers about the essay's original rhetorical context. This first version of the essay can then be compared with its subsequent appearances in variant editions. This online archive will be interactive, a site where scholars and others can meet, share syllabi, and discuss the essays.

Stuckey-French has also begun work on his next book project, tentatively titled Radical Middlebrow. This book will trace the progressive tradition in middlebrow culture not just through the work of essayists such as Richard Wright, Heywood Broun, and Dorothy Parker, but also through key moments in radio, film, television, and performance such as Marian Anderson's concert at the Lincoln Memorial on Easter Sunday 1939, and appearances by artists such as Katherine Dunham, Harry Belafonte, and Earth Kitt on the Ed Sullivan Show. He published a first piece of this work in middlebrow magazine and has a second article appearing this fall in Creative Nonfiction.