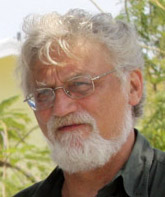

In a recent interview with National Public Radio, during an "All Things Considered" segment, Bob Shacochis talked about one particular difficulty he had while writing his newest novel, The Woman Who Lost Her Soul.

In a recent interview with National Public Radio, during an "All Things Considered" segment, Bob Shacochis talked about one particular difficulty he had while writing his newest novel, The Woman Who Lost Her Soul.

"I think the biggest challenge of the book, besides just the dread of doing the ugly sexuality and the violence—I mean, it felt like a type of punishment I had inflicted on myself—but the biggest challenge was to introduce a reader to a woman who is rather unappealing and reverse that reader's feeling about the woman by the end of the book," he said.

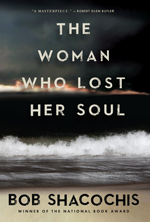

Based on the high praise Shacochis has been receiving for The Woman Who Lost Her Soul (Atlantic Monthly P, 2013), the English department's writer-in-residence not only met the challenge of introducing his main character but also found a spirit in his writing that has invited comparisons to other heavyweight authors.

Based on the high praise Shacochis has been receiving for The Woman Who Lost Her Soul (Atlantic Monthly P, 2013), the English department's writer-in-residence not only met the challenge of introducing his main character but also found a spirit in his writing that has invited comparisons to other heavyweight authors.

"A beautifully written, Norman Mailer-like treatise on international politics, secret wars, espionage, and terrorism… A brilliant book, likely to win prizes, with echoes of Joseph Conrad, Graham Greene, and John le Carré," reads a starred review on Booklist.

The Woman Who Lost Her Soul is separated into five sections, and Shacochis weaves his narrative through fifty-plus years, four countries, and several wars. His publisher describes the book as a "complex and disturbing story about the coming of age of America in a pre-9/11 world." The woman of the book's title is a photojournalist known as Jacqueline Scott to human rights lawyer Tom Harrington, who is the novel's first narrator. Scott (a.k.a. Dottie Chambers, among other names), is murdered in 1998 while visiting Haiti as an American tourist (traveling under yet a different name). An investigator asks Harrington to come to Haiti—a location that Shacochis knows well and covers extensively in his non-fiction account, The Immaculate Invasion—to help untangle the events leading to her death. Harrington's role in the narrative then fades away as Shacochis shifts his focus to Eville Burnett, an American Delta Force soldier.

Throughout the twists and turns in storytelling, Shacochis introduces readers to a world just as complex as the character who symbolizes the title; it is a "world … of secret Delta Force missions, of Pakistani peacekeeper/drug dealers, of mesmerizing Vodou priests, of Croatian revenge seekers, [and] of spies," as The New York Times reviewer Amy Wilentz writes. Ron Charles, a Washington Post reviewer adds, "Shacochis has choreographed a spellbinding dance of 20th-century atrocities and countermeasures to explore the foundations of America's millennial ambitions and the human cost of such hubris… Shacochis's approach is not outwardly theological, but, as the title suggests, The Woman Who Lost Her Soul is a novel invested in the health of souls… Sin, baptism, rebirth, resurrection—in these pages those theological terms are blessed by the sort of serious consideration that rarely has a prayer in contemporary literary fiction."

Shacochis told NPR that he considers himself "a writer who writes about American expatriates. And if I have any overt cause as a writer besides writing the best prose I can, it's to try to make Americans have a more visceral feeling about how America impacts everybody in the world."

And in a recent interview with the Los Angeles Review of Books, Shacochis said he foresees a long future for literary fiction, which "has forever been a specialty item in our society. It sells a certain amount and always will. It is, by nature, elite. It has a boutique consumer base. Just like the opera, it's not going anywhere."