Ph.D. candidate spotlight: Megharaj Adhikari, LMC Program

Note: Layne Roberts is a senior English-Literature, Media, and Culture major, and she will graduate in the Fall of 2025 with her Bachelor of Arts. She collaborated with Megharaj Adhikari on this profile and offered her own perspectives, shown here in italics.

Megharaj Adhikari, also known as Megha, is a doctoral candidate in the Department of English’s Literature, Media, and Culture Program. Born and raised in Nepal, Adhikari brings a rich background in literature, pedagogy, and cultural inquiry to his work at Florida State University.

Megharaj Adhikari, also known as Megha, is a doctoral candidate in the Department of English’s Literature, Media, and Culture Program. Born and raised in Nepal, Adhikari brings a rich background in literature, pedagogy, and cultural inquiry to his work at Florida State University.

Adhikari has been in the department since 2022. In that time, the department has awarded him the 2024 Dean’s Award of Doctoral Excellence and the 2023 Waters Fund for Excellence in Literature Award. In December 2023, the Modern Language Association elected Adhikari as a Professional-Issues Delegate of the MLA Delegate Assembly, a term that runs until January 2027. He also has been nominated for the MLA Executive Council for the 2025 MLA Election. Read more about that process here.

Through a question-and-answer format, he shares personal insights into his intellectual journey, the impact of positive mentorship, and some deeper ideas that highlight his scholarship through the years.

Could you share a bit about your academic journey from Nepal to FSU? What inspired you to pursue a Ph.D. in English with a focus on Literature, Media, and Culture?

My academic journey began in Nepal, where I taught English language and literature at both the bachelor’s and master’s levels. From early on, I was drawn to post-World War II American literature, particularly the Beat Generation. Their countercultural ethos and literary experimentation fascinated me. I think it was both aesthetic and political. There was also a personal layer; my professor in Nepal, Abhi Subedi, shared stories of his interactions with the hippies who had come to Kathmandu. He saw them as spiritual and cultural inheritors of the Beats. That sparked a deeper curiosity in me to trace the histories—both lived and literary—of those movements.

In 2012, I was selected for a virtual teacher training program by the American Institute at the University of Oregon, titled “Introduction to Online Learning for EFL Educators.” At that time, online education was still relatively unknown in Nepal. That course introduced me to digital pedagogies and the interdisciplinary strengths of American academia.

The defining moment came during the Fulbright-funded SUSI (Study of the U.S. Institute) program. I vividly remember a seminar by Dr. Aaron Jaffe on Pynchon’s The Crying of Lot 49 and Chandler’s “Red Wind.” His ability to interweave literature, media, and cultural psychology left a lasting impression. I turned to a colleague during that session and said, “If I ever pursue a Ph.D., I want to study under Dr. Jaffe’s mentorship.”

Years later, after teaching and reflecting, I applied to doctoral programs in the U.S. While I had other offers, my decision was clear—I wanted to study at Florida State University. The faculty here, especially Dr. Jaffe and Dr. Andrew Epstein, whose work I greatly admire, and the program’s strengths in 20th- and 21st-century American literature and cultural studies, made FSU the perfect place for me.

What does mentorship mean to you, both as a mentee and a mentor yourself?

Mentorship, to me, is sacred. I come from a lineage rooted in the guru-shishya tradition, where a teacher is more than an instructor—they are a moral guide and intellectual protector. In that tradition, the guru holds a status even higher than one’s parents. My father used to say, “You may disagree with me, but never disobey your guru.”

At FSU, I’ve found such mentorship in Dr. Jaffe. Our conversations often reflect on the long view of mentorship—how scholarly traditions are passed down and reinterpreted. Dr. Jaffe’s stories about his own mentors, such as Stephen Watt [Professor Emeritus of English at Indiana University] and Cary Wolfe [Professor Emeritus of English at Rice University], reinforced my belief that mentorship is a form of intellectual stewardship. It’s about nurturing future scholars who will, in turn, continue that legacy.

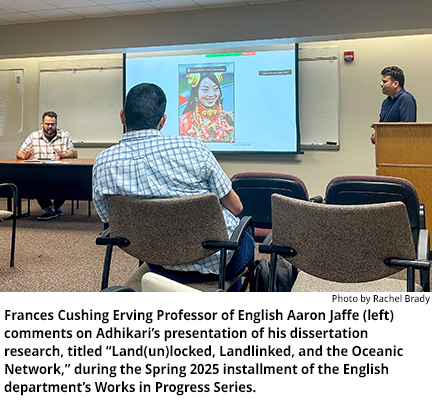

The inspiration Adhikari draws from Frances Cushing Ervin Professor Aaron Jaffe and Caldwell Professor and department Chair Andrew Epstein shows the commitment English faculty members give to students from such rich and far-reaching backgrounds. Adhikari speaks highly of his admiration for FSU and the entire department, including the staff and his graduate program colleagues.

You had already established yourself as a scholar and teacher in Nepal before coming to FSU. How has that experience shaped your approach to research and teaching here?

Teaching in Nepal gave me strong foundational skills, especially in managing large classes and delivering content through extended lectures. I was used to speaking for 90 minutes straight. That gave me confidence and clarity. But when I began teaching at FSU, I encountered a very different model—dialogic learning, flatter hierarchies, and active student participation. Here, teaching feels more collaborative, like a shared intellectual exploration rather than a one- way transmission of knowledge. That shift reshaped my pedagogy. I now strive to blend both approaches—bringing the structure and discipline from my earlier experience together with the openness and inquiry that define U.S. classrooms.

What do you enjoy most about teaching in the English department at FSU?

I genuinely enjoy working with FSU undergraduates. Their curiosity, energy, and openness to new ideas are infectious. During my first two years, I taught first-year writing courses. Students often become more engaged when I share cultural or academic experiences from Nepal—it creates a dialogue that goes beyond the syllabus.

Now that I’m teaching literature, particularly Asian American literature, I find even greater resonance with my interest in transnational narratives. The classroom becomes a space of shared curiosity and cultural exchange, which is deeply rewarding.

Adhikari’s transition to U.S. classrooms from his diverse educational background in Nepal is fascinating from an outside perspective. His 90-minute seminars at FSU challenge his strengths and skills, especially when held in a different classroom environment. This flexibility and openness as a scholar, however, continue to help him grow and learn, as he moves toward his career goal of becoming a professor or a similar academic role.

What drew you to examine Nepal’s historical and physical connections to the Indian Ocean?

That’s a question close to my heart. From a young age, my grandfather, a Sanskrit scholar, taught me that conventions are constructed—they tell stories about truth but aren't truth themselves. That planted in me a lifelong skepticism of taken-for-granted categories.

In Nepal, there's a common narrative that the country is economically disadvantaged because it's “landlocked.” But I began to ask—who defines these terms, and to what end? I discovered that binaries like “landlocked” vs. “littoral” are rooted in colonial and cartographic ideologies that serve strategic and extractive purposes.

Through the framework of elemental media—earth, water, air, fire, ether—I began to see these binaries collapse. Nepal is not isolated; it contributes materially to the Indian Ocean world through its rivers and the Himalayan ecosystem. My current work argues that understanding Nepal’s place in this interconnected network is crucial, and I presented this in a talk titled “Land(un)locked, Landlinked, and the Oceanic Network.”

The personal aspect of Adhikari’s career may seem like a small detail to outside observers, but this connection to family and place clearly shapes the inspirations behind his work.

How do you see your dissertation research contributing to broader conversations in modernist and postcolonial studies?

My work tries to dismantle the binary between elevation and depth. There’s a tendency to see the peak as a symbol of triumph and the delta or depth as a limitation. But from a geological perspective—what John McPhee calls “deep time”—these are not fixed. The summit of Mt. Everest is marine limestone. So, what we see as the highest point was once part of the ocean floor.

This challenges colonial mapping practices, which often impose artificial hierarchies on geography. Naming the peak “Everest” is itself a colonial gesture—mapping as ownership. I argue for a more ecological and ethical understanding of nature—one that acknowledges relationality and interdependence rather than separation and dominance.”

Is there a particular insight in your research that surprised you or changed your assumptions?

Yes—one conceptual discovery deeply surprised me. I was looking at the symbolic representations of the peak and the delta. Both are drawn as triangular icons: the peak pointing up, the delta down. If placed together, they form a hexagram or mandala—a sacred geometric form in many traditions.

In Eastern philosophy, this mandala, called Shanmukha, represents the fusion of masculine and feminine energies, creation, and cosmic balance. I realized that this symbol is revered across Hindu, Buddhist, Christian, Jewish, and Islamic traditions. That convergence made me think— perhaps these geographies (elevation and delta) are not as opposed as we assume. Their differences are constructed. They are, in essence, expressions of the same elemental processes. This insight is now helping me think more deeply about the symbolic and cognitive systems we use to divide what is inherently unified.

Outside of research and teaching, what are your hobbies or personal interests?

Outside of research and teaching, what are your hobbies or personal interests?

I enjoy traveling, although I haven’t had much chance to do that since joining FSU. Most of my free time is spent with my two wonderful children. Weekends are often reserved for long FaceTime calls with my grandfather, parents, siblings, and nieces back home in Nepal.

During the pandemic, I developed a habit of listening to podcasts—especially those that explore philosophical or cultural themes. I also find deep joy in reading ancient epics like the Ramayana and Mahabharata. They’re reservoirs of wisdom that continue to inspire me.

What are your hopes for the future—as a scholar and academic?

My hope is to contribute to a more inclusive and interconnected understanding of literature, media, and cultural history—particularly by bringing in perspectives that are often marginalized. I want to continue challenging inherited binaries and exploring the networks—ecological, historical, and intellectual—that connect us. Ultimately, I see scholarship as a bridge across worlds, and I hope to help build those bridges with care, rigor, and humility.

Adhikari’s international experience is intriguing and encouraging. He is a scholar, teacher, and mentor, someone who can be seen as a positive representation for English majors. His research challenges conventional ideas about geography and culture while also demonstrating his resilience in the face of change. As a scholar, he has unique interests that drive his research and academic pursuits.

He is inspiring to me, an undergraduate in the English-Literature, Media, and Culture Program, because of the experiences he has gained and the way he graciously speaks about them. His influence on the English department, whether he is working with professors, his peers, or undergraduates, is visible through the effort he has put into his studies and his teaching. I hope to be a student in FSU’s graduate program, specifically with a focus on teaching in the future, and I appreciate Adhikari’s insights and opinions on mentorship, as well as his positive interactions in the department.

Follow the English department on Instagram; on Facebook; and on X.