Associate Professor Michael Neal delivers talk on Generative AI, plagiarism at Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning Expo 25

By Rachel Brady

Florida State University and Tallahassee's Challenger Learning Center recently collaborated to bring together experts on artificial intelligence and machine learning to discuss the ethics and applications of the technology in academics.

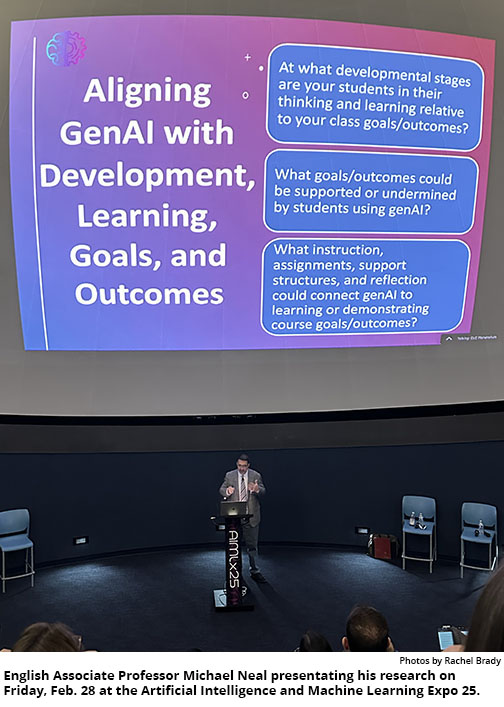

English Associate Professor Michael Neal was one of several FSU faculty members who presented their research Friday, Feb. 28 at the Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning Expo 25.  Neal’s presentation, “Decoupling Generative AI from Plagiarism: Toward a New Model of Authorship and Intellectual Property for Student Writers,” provided a framework for educators to consider for using genAI in the classroom.

Neal’s presentation, “Decoupling Generative AI from Plagiarism: Toward a New Model of Authorship and Intellectual Property for Student Writers,” provided a framework for educators to consider for using genAI in the classroom.

FSU’s Interdisciplinary Data Science Master's Degree program hosted the event, and faculty and students filled the Challenger Learning Center planetarium, notepads ready to record Neal’s insights.

“I think we have to align genAI with certain developmental learning goals and outcomes,” Neal said.

Not every discipline will use genAI in the same way, he added, so the rules and expectations need to be made clear for each class and assignment. Neal suggested that educators consider their students’ developmental stages and the learning goals of the class to determine if and when AI use is appropriate.

Students’ critical thinking skills are a highly discussed aspect of genAI’s use in the classroom.

“For me, critical thinking is students communicating more deeply beyond simplistic binaries to develop complex and nuanced positions and ideas,” Neal said during his presentation. “And so, I have to ask myself, will using AI in a particular place encourage that kind of critical thinking? It can in some contexts, I believe, and it could undermine them in another context.”

Context is important to the discussion. Neal is a professor in the department’s Rhetoric and Composition Program, and he explored how writing functions as a component of thinking and learning during his talk.

“Writing to learn is a kind of writing in which we don’t make the assumption that we have it all figured out, and then we transcribe it to the paper,” said Neal, adding that the process of writing is the goal, not the finished product.

“Notice here, there's really nothing on this slide about the ability to produce polished text,” says Neal, gesturing to a slide that describes important functions of writing in college classes.

Some of the ways Neal uses genAI in his classes are invention activities, comparative analyses between genAI and students’ work, writing prompts, feedback questions, and most importantly, students’ reflecting on their work with and without AI.

“For me, a polished, final text could but doesn’t necessarily represent a student’s learning,” Neal said. “If that product is there, but it doesn’t represent their learning, then AI has undermined that process and the measure.”

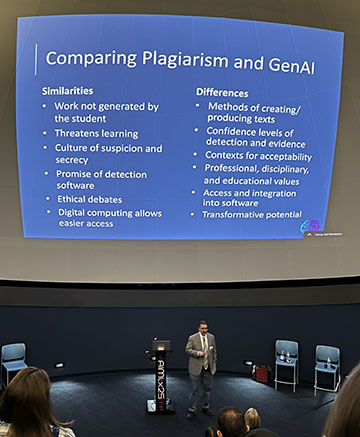

Because there are similarities between plagiarism and genAI—namely that the students haven’t produced the text themselves—it’s easy for students and faculty to conflate them. However, there are significant differences between them as well, such as genAI’s acceptance and use in many fields of study and in professional environments.

Neal invited audience members to reconsider their definition of plagiarism.

“The way we construct plagiarism assumes that we can draw these very clear lines between what’s mine and what’s somebody else’s,” said Neal, asking the audience to think of plagiarism instead as a continuum. "Plagiarism assumes that there are very clear distinctions between students’ work and external sources."

“The way we construct plagiarism assumes that we can draw these very clear lines between what’s mine and what’s somebody else’s,” said Neal, asking the audience to think of plagiarism instead as a continuum. "Plagiarism assumes that there are very clear distinctions between students’ work and external sources."

“It’s actually much blurrier than that, and I think we’re going to find that AI is that way.”

The same could be said of students’ writing with AI, where instructors would like to see clear distinctions between student and machine writing, but that line is also blurred with the ways AI is integrated in the writing technologies and processes.

During his discussion, Neal displayed a slide with a list of ways students might use genAI over a continuum that ranged from academic dishonesty to acceptable practice. He included items from prompting genAI to write the full text to asking it questions about a human-generated text.

Another slide displayed a similar continuum but with items unrelated to genAI, such as copying someone else’s paper to asking a teacher for help with an assignment. He noted that reasonable people across campus could have very different places they would place these activities, which is why clearly defining boundaries and expectations for students is so important.

To reimagine writing in a way that acknowledges the blurriness of these boundaries, Neal used Kirby Ferguson’s Remix theory, which states that creativity is the process of copying, transforming, and combining works a person is already familiar with. Neal used language as an example.

"People learn to speak by copying and imitating other people’s speech," Neal says, "and eventually, reconfiguring it to make it their own. In this way, people learn through imitation, by copying."

Throughout a person’s life, he added, they read and listen to millions of words and ideas to the point that they could never remember where they all came from, which makes perfect citation impossible. But that’s learning, not plagiarism.

“In part, we’re all copying, but we’re not plagiarizing,” Neal said. "This is the reason why it’s so important for students to read and fill their minds with well-reasoned and complex texts. We’re copying in the sense that we’re filling our minds with good texts, and we are transforming those texts for different audiences and different contexts."

When we fill our minds with simplistic, poorly constructed texts, it’s not surprising that we reproduce weak writing, he explained, which is not unlike what is happening with training large language models (LLMs) with genAI.

Neal’s final charge was to integrate genAI into the classroom in ways that distinguish it from how we’ve approached plagiarism.

“I’m not interested in more detection software,” Neal said. “I’m not interested in all this work we do that’s about policing and not trusting students. Maybe we need to let our assignments evolve to meet the technology, instead of trying to keep our students from using the technology that we have.”

Neal’s presentation highlighted the idea that while genAI has the potential to undermine student development and learning, educators need to determine when and how students can use AI to support learning goals and outcomes, affirming the critical roles humans will continue to have in writing, learning, and critical thinking.

Rachel Brady is an English-Editing, Writing, and Media major, with a minor in innovation.

Follow the English department on Instagram; on Facebook; and on X.