English undergraduate major Sydney Richner went 'inside' with SER editors for the magazine's incarcerated writers workshop

By Sydney Richner

Exchange for Change is a South Florida-based organization that offers courses to and facilitates letter exchanges between incarcerated students and students on the “outside.”

“It’s easy for someone to think that people in prison have more to learn from me than I do from them, until they actually go inside,” Florida Atlantic University Associate Professor of English Wendy Hinshaw says. She is a founding board member of Exchange for Change, and she also is a mentor of mine.

Hinshaw’s experiences and guidance provided relevant context for me when I joined four staff members of Florida State University’s nationally recognized literary magazine Southeast Review in March of 2023 for an incarcerated writers workshop.

All of us experienced the “inside” of the Gadsden Correctional Facility, a private state prison for women located in Quincy, Florida, to lead two creative writing workshops. Alyssa Freeman-Moser, a Master of Fine Arts student in English-Creative Writing, Maggie Smith and Anthony Borruso, doctoral students in English-Creative Writing, and Brett Hanley, an FSU alumna with her doctorate in English-Creative Writing, all represented SER.

Going into the workshops, I knew that a felony charge follows a person for the rest of their life. Beyond the permanent legal restrictions that come with convictions, there is a societal stigma or “prison label” that no amount of time served will rectify. Despite the purport of prisons being focused on reformation, imprisoned individuals can be considered “dangerous,” marked, and dehumanized indefinitely.

Once inside the facility, I wanted to avoid furthering offender alienation; however, I admittedly went into the workshop with assumptions about who the incarcerated are and feelings of nervousness surrounding their relatability, personability, and writing capabilities.

Getting to know these women—their stories, interests, and creative ambitions has been one of my favorite and most fulfilling experiences as a graduate student and one that has really opened my eyes to the struggles of some of our society’s most marginalized.

— Anthony Borruso

My socially conditioned biases were extremely unwarranted. From the moment the first workshop started, the women at Gadsden were instantly engaged, eager, and equally knowledgeable about creative writing in their own right.

“Getting to know these women—their stories, interests, and creative ambitions has been one of my favorite and most fulfilling experiences as a graduate student and one that has really opened my eyes to the struggles of some of our society’s most marginalized,” says Borruso, who is one of SER’s poetry editor. “What stands out to me especially is the joyful greetings and rapt attention we receive upon each visit.”

During the workshops, the women were extroverted, friendly characters, whose enthusiasm to participate felt contagious. By the second and final workshop, Borruso, Smith—who is an SER nonfiction editor—and I found ourselves sitting in an intimate, talking circle with our students.

The SER team chose the central theme of the workshops: constraints in writing. I was surprised at how optimistically the attendees framed constraints, considering their living conditions. There was discussion about how sometimes constraints enable the writer to avoid writer’s block or to flourish in adversity. Similarly, they talked about how prison has allowed them a break to focus on themselves; this line of commentary felt less like a romanticization of incarceration and more like a coping mechanism or survival outlook.

In reference to Karisma Price’s poem “And,” which was read at the first workshop, Borruso says, “I think what stands out to me about these lines is how they manage to find tenderness and beauty in the harshest of conditions–something which, I believe, the women of Gadsden Correctional manage to do on a daily basis.”

What came as a shock during the workshops was how relatable the Gadsden women felt to me. From their personal anecdotes—detailing heating pads or calls to family members, among other topics—to their writing results, I realized the extent to their humanity: they are people, first and foremost, beyond their convictions.

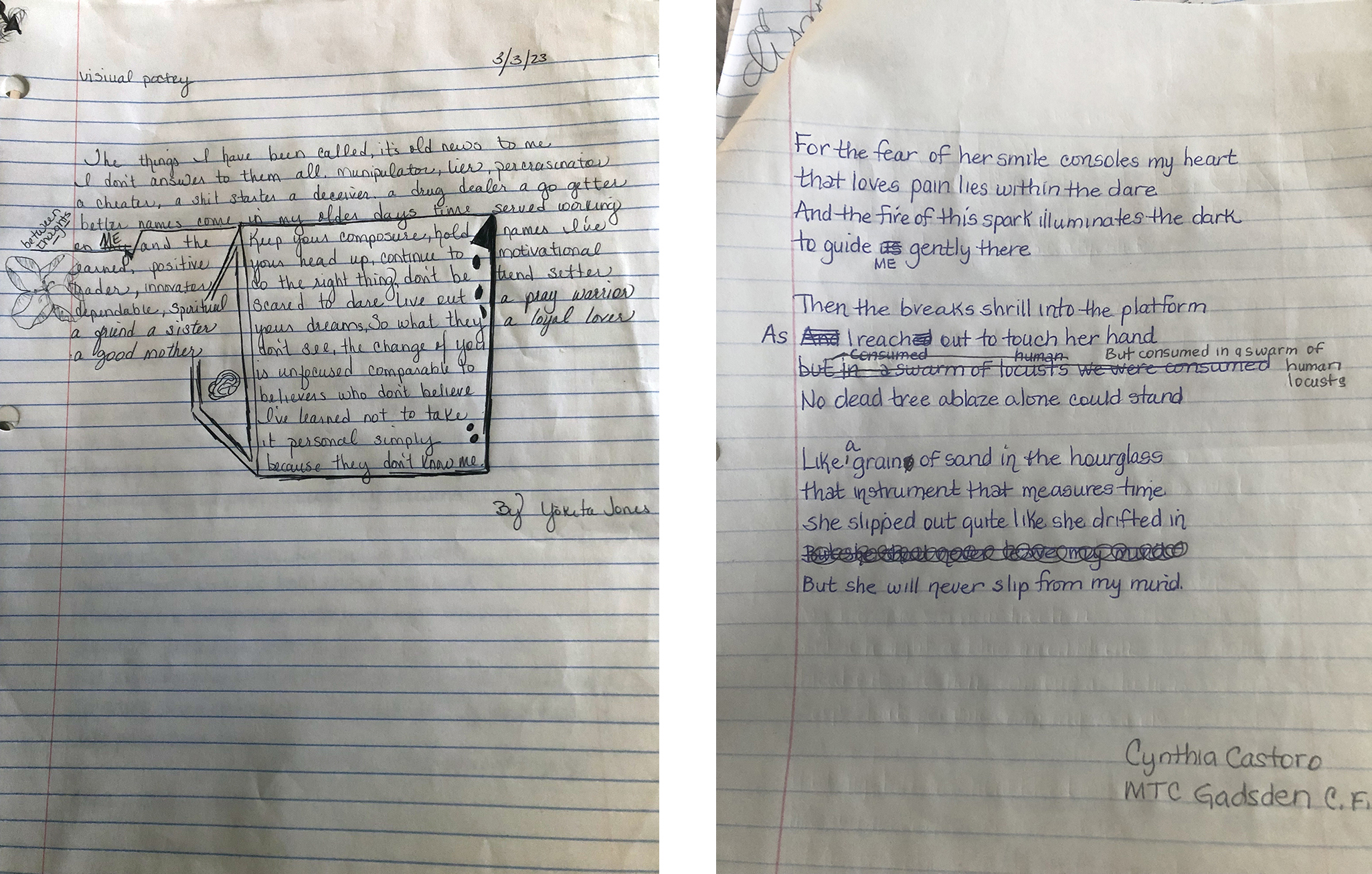

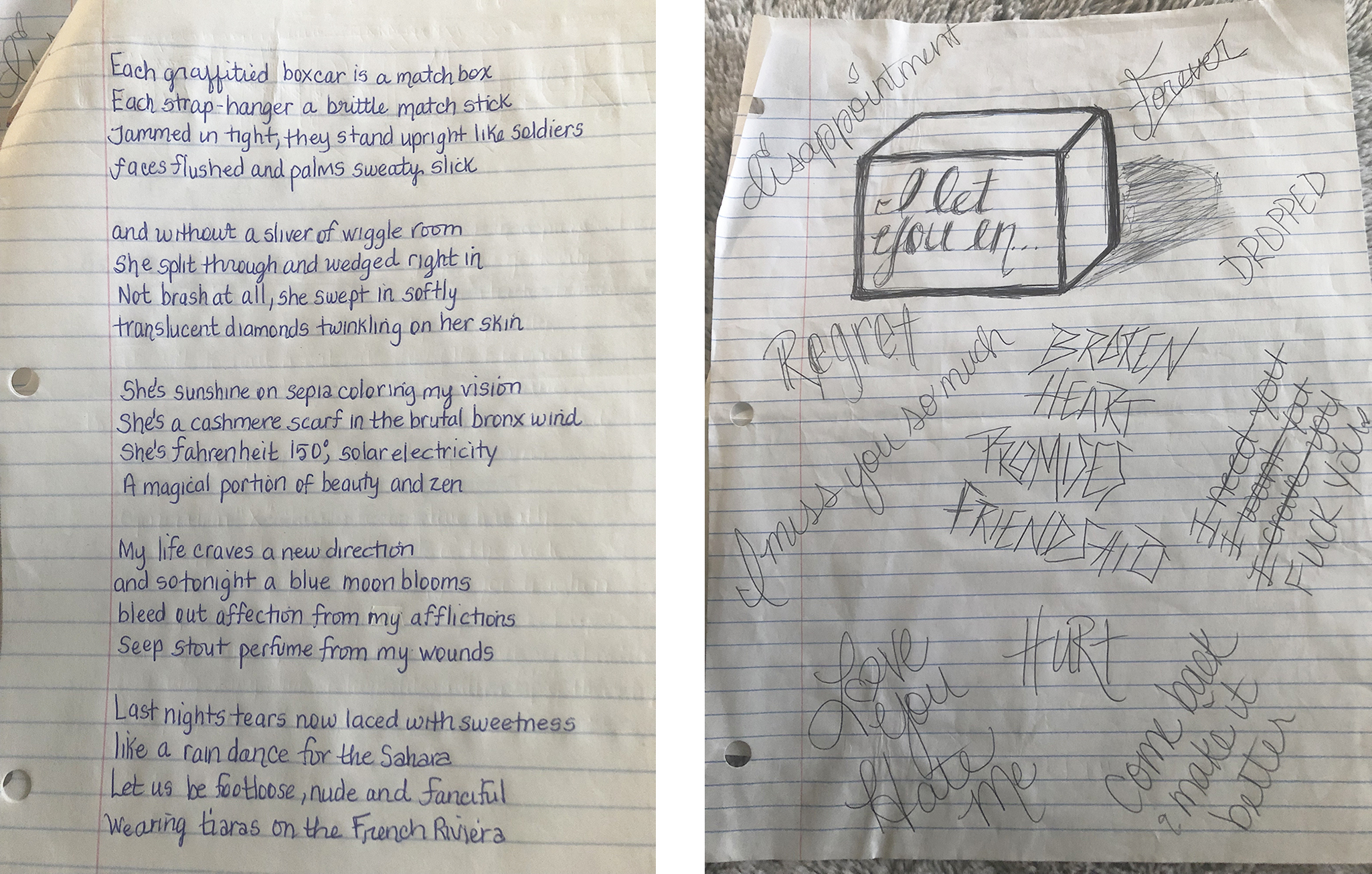

In working with the workshops’ theme, constraints, the SER editors proposed a prompt to draw a box on a page and instructed the group to subsequently use that box to fabricate a creative work. The works by Cynthia Castoro and Yokita Jones, two of the women who are incarcerated at Gadsden, as well as a third woman who asked to remain anonymous, each respectively touched me.

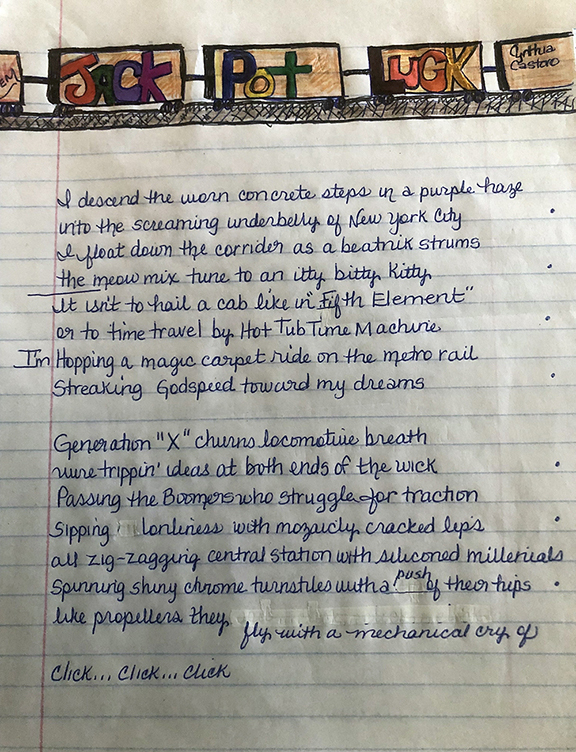

The anonymous author constrained herself through her incorporation of single words, rather than phrases. Jones implemented the box as a representation of headspace, condemnations from others being external to the box and thoughts and ideas of  self-worth being contained within it. Castoro used the box prompt as a springboard to create a train that represented the haze of love and longing. (See other images included with this article at the end.)

self-worth being contained within it. Castoro used the box prompt as a springboard to create a train that represented the haze of love and longing. (See other images included with this article at the end.)

What amazed me most was their ability to draw on the literature we provided to cultivate an atmosphere equally inflected by curiosity and by generosity.

— Maggie Smith

How these women captured their human experience—similar to my own—in their own unique ways, without much direction or critique other than open ears, was remarkable to me.

“What amazed me most was their ability to draw on the literature we provided to cultivate an atmosphere equally inflected by curiosity and by generosity,” Smith says. “For my money, these are also the most important aspects of being a human in community with others.”

The misconceptions and assumptions that I carried surrounding people convicted of a crime, however subconsciously, result in socioeconomic disparities. Writing workshops, such as SER’s, enable incarcerated individuals to gain the skills they need for rehabilitation and, most significantly, instill a confidence in justice-involved students as equally qualified writers.

Since Exchange for Change began offering their workshops, “seventy-five percent of participants report a positive shift in attitude regarding their ability to use writing and the arts to affect change in their community and seventy-five percent report gains in knowledge of the material,” FAU’s Hinshaw says. “There’s something really powerful about being able to interact on a page.”

Prison-writing enables writers on the inside to do more than express themselves; the process serves to teach those on the outside as well. I know I learned just as much from my experience with Gadsden’s writers as they did from the SER team and me.

From the women’s willingness to contribute their perceptions of temporality, restrictions, and mortality, they made every second of the workshops worth the visit.

Sydney Richner is an English major in the Literature, Media, and Culture Program with a minor in sociology.

Follow the English department on Instagram; on Facebook; and on X.